My favorite section of the Sunday New York Times is the Book Review. Even back when I was practicing law in Manhattan as a corporate attorney, knowing I should be turning first to the business section, knowing that my livelihood depended on understanding, for example, what cell towers were, I couldn’t help it. Yes, that was back when banks were financing the construction of cell towers and I had no idea what they were, but I didn’t really care. What I cared about was what book I should read next, and later, when I began writing, what I could learn from other writers.

I’d peruse the book reviews of new releases and the bestseller list. But before that, I would turn to the section where they ask an author a series of questions.

It didn’t matter if the author was someone I had already read or not. And I admit the question sometimes felt a little bit like celebrity interviews. I always felt like there was some answer to one of the questions that would inspire me and send me in some new direction.

As I see it, the questions posed by the New York Times basically fall into three categories:

1. Questions about the author’s writing or reading process.

2. Questions about what books the author has read or recommends.

3. Quirky questions. One of my favorites in the New York Times is “you’re having a literary dinner party. What three people would you invite?”

When asked about their writing process, some authors answer that they get up at four in the morning and write for two hours, or they write during their lunch break at the office, or they write in coffee shops. How does it affect the writing--whether the writer was in a sundrenched room overlooking an apple orchard or staring at a concrete wall?

One woman I heard at a conference said she wrote in her basement with a blindfold, typing away at a laptop without being able to see what she was writing. Now let’s assume that method of writing worked for her. I assume it did or she wouldn’t do it. Am I to conclude that if I went down to my basement and put on a blindfold that I would suddenly become a different or perhaps better writer?

What are they reading, or wanting to read, or regret not having read? This idea leads to asking an author what books are on their bedside table or what book everyone should read. Questions such as “what great book have you not read yet” gives me pleasure when I can check off some important book that I’ve already read, but I have a sneaking suspicion that my delight does not have much to do with whether I’m a good reader or writer. The question is designed I suppose to make our author look a bit humble or perhaps chagrined by saying they’ve never read Proust or The Brothers Karamazov, but does this really make us like them more or want to read their books? Do we really think this is true or simply false modesty?

The final one in most interviews is what three authors--living or dead-- would you invite to have to join for dinner? Virginia Wolf often figures prominently on the list. But what I’m even more interested in than whether the authors eat shrimp cocktail or sip Campari is why the author would choose to put these people together. What makes them fascinating company? What would they love about meeting each other?

Also, I want to know the backstory behind the author’s latest book, how they came to write it and what they hoped the reader would take away from it.

And just when I’m criticizing the New York Times for being predictable, I see today that it has added some new questions and removed some of the ones I object to. In its interview with V E Schwab, author of “Bury Our Bones in the Midnight Soil,” which is on the bestseller list, the Times added a new question: “how have your reading tastes changed overtime?” Also, “Is there a book in your vast output that you wish you could rewrite? (Schwab said no) And finally “How do you sign books for your fans? (She avoided the question by answering that she had agreed to sign the first printing of her book which took her 2.5 months to sign 300,000 copies. )

Poets and Writers Magazine has ten questions they pose to all authors they interview. The questions balance appealing to both readers and writers. Here they are (lightly edited):

1. How long did it take you to write your book?

2. What was the most challenging thing about it?

3. Where when and how often do you write for?

4. What are you reading right now?

5. What author deserves wider recognition?

6. What is the biggest impediment to your writing life?

7. What is one thing your agent or editor told you that stuck with you?

8. If you could talk to the earlier you before you wrote this book what would you say?

9. Outside of writing, what other forms of work were essential to writing your book?

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

I am intrigued by answers to the question about advice. Perhaps it’s obvious that authors would only talk about advice that they’ve actually taken, but I would be interested to know what advice you’ve been given that you didn’t take and why.

Sari Botton publishes a number of questionnaires on Substack, including one called “Memoir Land,” (memoirland.substack.com) which includes 14 questions.

Here are a couple of my favorite questions:

1. What is the elevator pitch for your book? An elevator pitch is a short way of explaining what a book is about to an imagined agent or editor, who you meet in an elevator, giving you only enough time to explain it before the fourth floor dings. It’s a great way to hear what an author thinks is most important about their book.

2. “Who is another writer you took inspiration from” which is interesting in trying to decide whether I want to read this particular writer. It differs from “what’s on your nightstand” because the writer connects the book with inspiration.

3. Are there non-writing activities that support your writing?

4. What do you love about writing?

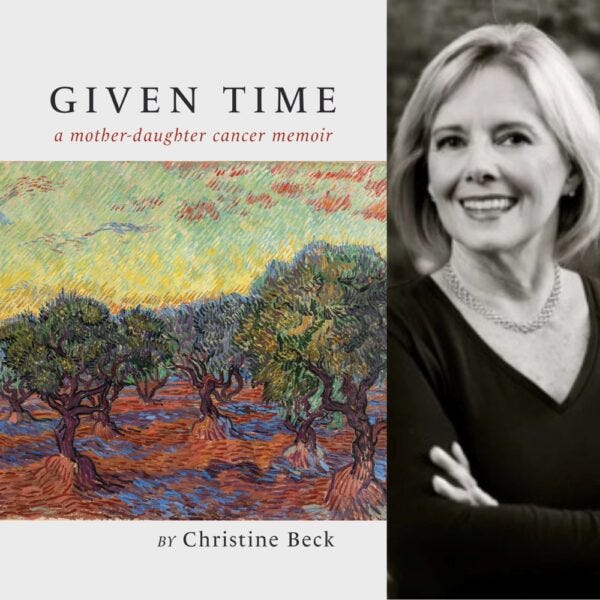

I decided to take my own advice and answer questions I think are most meaningful for my book called “Given Time,” which will be released in July.

1.What is the elevator pitch for your book?

Given time is a memoir in poetry about the breast cancer of Christine Beck‘s mother and her own recent diagnosis. These poems, juxtapose loss and hope, then and now, and two women – mother and daughter – as they twine their lives together, much like the trunks of the olive trees painted by Van Gogh This collection resounds with the awareness that we all offer gifts to those. we love. Some we recognized at the time if we’re lucky. Some we don’t see until we are far apart. Christine Beck and her mother live in these pages as the vibrant spirits they were and continue to be. Like yarn carried on the underside of an intricate knitted pattern, they are “linked by strands of pink.

My mother and I on a trip to Spain.

2.How long did it take you to write this book?

My initial poems in this book were written shortly after I started writing poetry in the year 2000. At that point I was writing about my mother‘s death from breast cancer in 1978. My diagnosis was in December 2022, so the second half of the book was written much more recently. The poems in Part II echo themes, images and sometimes lines from those in Part I.

2.How does your lived experience show up in your book, including your origin story as a writer?

The backstory was my relationship with my mother and going through her breast cancer by her side. In the year 2000, I gave up practicing law and turned to writing poetry. Looking back, I can see that some pivotal themes emerged from my writing at that time. One of them was my difficult childhood as the child of an alcoholic father. Another was my mother converting to be a Jehovah’s Witness, and the third was losing my mother to cancer when I was 30 in 1978.

3. If you could talk to the earlier you before you wrote this book, what would you say?

I would tell that earlier me that you will write when you are ready. In 1998, I took my first creative writing class and recall telling the instructor, “I don’t have any stories to tell.” Then I didn’t. Now I do. I’d also tell myself: Find writer groups to inspire you and help you develop your craft. Read widely. It will all come together just the way it should.

4. What’s the best piece of advice you’ve ever been given?

Shortly after my first daughter was born. I took six weeks of maternity. Leave from my job as a lawyer in a corporate law firm emerging from lunch with a group of women friends on my first day back, I admitted that I wasn’t sure I could go back to working full-time. A friend said to me “just quit. You’ll never regret the time you spend with your child. “As it turned out I was able to work part time for my firm, but that advice has stuck with me.

5. You’re organizing a literary dinner party which three writers, dead or alive, do you invite? I’d choose writers from different countries with strong points of view. Robertson Davies, the delightful Canadian author of The Salterton Trilogy for his wit and expansive view of human nature; Louise Erdrich, because I love how she mixes Native American lore and mysticism into her novels; Elif Shafak, the Turkish author now living in London, who most recently wrote “There Are Rivers in the Sky” because she blends magic realism with issues of justice and genocide. Finally, I’d add in John Banville, who wrote “The Sea,” my favorite book, because he’s Irish and I love his language. (That’s 4 people, but I’ve always had a hard time following directions. )

6. What do you hope readers will take away from your book? In an article this week entitled “Character Study,” Ricardo Tomas in the New York Times Magazine examines biography. He quotes Richard Ellman, who wrote a biography of James Joyce in 1959: “the effort to come close to make out of apparently haphazard circumstances a plotted circle, to know another person who has lived as well as we know a character in fiction…It may even be, for reader as for writer, an essential part of experience.”

Tomas sums up this “plotted circle,” by asking: Did it [the biography] allow him to write out the human problem in a way that we, following on four hundred years later [about John Dunne] can still find urgent truth in it?”

I hope the urgent truth that emerges from “Given Time” is that death releases memories of people we love from a final illness or old age. I hope readers enjoy a portrait of both of us painted with love, grief, and the rare connection between us, both when she was alive and today.

hiChristine - do you know sandy yanone and her wonderful Cultivating Voices on line poetry meetings - they showcase new books for people who come from time to time - I'm sure they would showcase yours too if you come and see how it works out

Writing about a relationship with a mother is so complex. I am doing so from a very different perspective and in a novel, rather than poems, but I agree that you write when you are ready. There's so much to express that sometimes it has to be done between the lines.