Every once in a while, I become fixated on how I found a particular book. It doesn’t really matter, I tell myself, but I simply must know who recommended it or where I found the reference. In the case of “The Island of Missing Trees,” by Elif Shafak, I cannot tell you how I came across the book, but I can say that had I not read it, I probably would not have eagerly awaited Shafak’s latest, which is called “There are Rivers in the Sky.” I’m glad I did.

Now I am convinced that someday I will meet Elif Shafak, even though she lives in the UK and is 20 years younger than I am and is famous.

You know that column in the New York Times Book Review where an author asks who they would invite to a small dinner party? Shafak would definitely be on my list. She feels to me like someone who will complete a missing part of me. This is perhaps no more far-fetched a proposition than that one drop of water travelled from Nineveh in 630 BC to the sea outside London in 2018.

I am entranced by “There Are Rivers in the Sky.” It has taken me down numerous rabbit holes of internet research. As with all historical fiction, I want to learn how much is based on fact and how much imagined. Fortunately for us, Shafak answers most of those questions in the endnotes. These endnotes are extensive, in over six dense pages. In the Audible version, they are read by Shafak, a lovely treat.

A great deal of this novel is based on fact, yet Shafak’s unique sensibility frequently spins those facts into unexpected directions. The narrative spans centuries—from the earliest known piece of literature to a genocide in 2014. Shafak weaves historical fact with image and detail that compel the reader to turn the page. The novel teems with big ideas. In fact, there are so many big ideas that once I finished listening to the book on Audible, I ordered a paper copy to review the parts that particularly compelled me. I imagine I will be writing about this novel for weeks to come.

What I want to talk about this week is the central theme of the novel, which is water and the idea that every drop of water connects people and places over time. The novel takes place in three timeframes near the banks of two rivers. The first river is the Thames in London -- the site of an 1800s narrative about a young man who deciphers cuneiform tablets written during the reign of King Asurbanipal of Nineveh. (There were 15,000 fragments).The River Thames also features in a modern-day narrative of Zaleekah, a hydrologist who has just left her husband and is drifting living on a barren houseboat. The final narrative takes place in 2014 when Narin, a young Yazidi girl, travels from Turkey to Iraq to be baptized in her faith ,with disastrous consequences.

The rivers, the life of rivers and the power of water are central to all of the narratives. Such is the power of rivers:

“When King Galgamesh died, they interred his body under the river. Not inside, but under. To do this they had to divert the Euphrates, forcing it to flow in an unnatural direction; once the funeral was over, they returned the river to its original course. The workers who dug the hero’s grave were all killed afterward. That way, there would be no one left alive to reveal the burial place.”

The main character, who decodes the cuneiform tablets, is called King Arthur of the Sewers and Slums. He is born of a poverty-stricken mother who ekes out a living by pawing through the muddy banks of the garbage strewn sewer that was then the river Thames for minor items of value. King Arthur of the Sewers and Slums is based on a real character named George Smith, also born in poverty, who became famous for deciphering the oldest piece of literature in the world, the epic of a Gilgamesh, which was written in cuneiform between 2050 and 1400 B.C.

Gilgamesh is an epic comprised of a king, wild animals, a search for immortality, an enemy turned friend named Enkidu, and mercurial gods. I first heard of it in a poetry conference twenty years ago and was abashed that I didn’t know the oldest poem written.

Part of the difficulty in deciphering cuneiform was that it is not a one-on-one correspondence to either letters of any known alphabet or to sounds. It is more like a pictograph of phrases or ideas. The phrase could only be determined from context, and in order to determine context, Arthur looked for similar symbols in items as basic as bills of sale and then built a knowledge base from there.

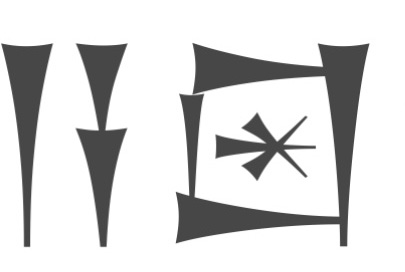

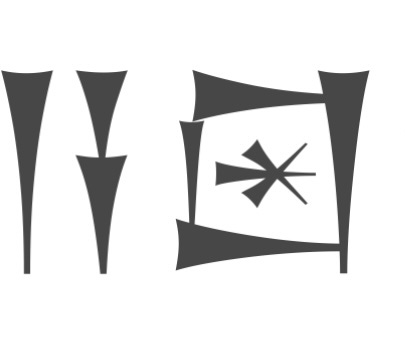

Here are the cuneiform symbols for water and for river.

The Epic of Gilgamesh contains a narrative of a flood that destroys mankind, leading to questions as to whether the Biblical flood story was based on the earlier Babylonian story. I’ve already been down the rabbit hole, reading a comparison of the Bible to the stories in Gilgamesh, which I’m sure Shafak has also done.

This issue caused a stir in British society when Arthur lectured to a learned crowd, including the Prime Minister. It led to him raising funds to mount excavations to Nineveh to hunt for missing cuneiform tablets. (All true. This happened to George Smith.)

The central conceit that runs through “There Are Rivers in the Sky” is that a single drop of water can travel across time and countries as a unifying force. At the end of the book, there is a spreadsheet called “The Journey of a Drop of Water” beginning in 630 B.C. with a snowdrop that falls on the head of King Ashurbanipal in Nineveh and ends in the ocean outside London in 2018. This calls for a suspension of disbelief. When a drop of snow lands in Arthur’s mouth when he is born, how does it then get into the English Channel? And how is that measured in time?

Remember, Shafak wrote a novel with a talking fig tree, also a hypothesis born of magic realism. This hypothesis assumes that water is a witness to all of life’s events from the horrific burning alive of Asherbanipal‘s mentor in chapter 1 to the brutal genocide by Isis of the Yazidi people in Iraq, which takes place near the end of the novel.

However, there is another theory about water that figures in the novel set in modern-day London. Zaleekah’s mentor, Professor Berenberg posits a theory of “aquatic memory,” that water retains evidence, or memory, of the solute particles that had dissolved in it, no matter how many times it was diluted or purified. I assume Shafak took this hypothesis from a current scientific experiment which has been discredited, as was Berenberg’s in the novel.

In a 2021 article in the journal “Explore,” Francis Beauvais stated:

The controversy over the “memory of water” that burst in 1988 continues to maintain in the shadow the whole story of Benveniste's experiments that extended over 20 years from 1984 to 2004. Admittedly these claims were anything but insignificant: the experiments presented in Nature suggested the existence of molecular-like effects in the absence of molecules. The authors of this article stated that dilutions of biologically-active molecules beyond the limit defined by the Avogadro number had nevertheless a biological effect.

The violence of the controversy had most probably its roots in the “two centuries of observation and rationalization” that these results were supposed to reconsider.Because the idea that a “structuration” of water could mimic the effects of biologically-active molecules was considered impossible, the inevitable conclusion was that the experiments were flawed. As a consequence, there was no place for an alternate theoretical framework that would consider these results, without involving water and its alleged “memory”. The fact that this study could support homeopathy, also highly controversial, was another reason for this strong opposition.

If this article sounds “dry,” as academic articles often do, look at Shafak’s lyrical language about the power of rivers:

“Rivers are fluid bridges—channels of communication between separate worlds. They link one bank to the other, the past to the future, the spring to the delta, earthlings to celestial beings, the visible to the invisible, and, ultimately, the living to the dead. They carry the spirits of the departed into the netherworld, and occasionally bring them back. In the sweeping currents and tidal pools shelter the secrets of foregone ages. The ripples on the surface of water are the scars of a river. There are wounds in its shadowy depths that even time cannot heal.”

The drop of water is also a literal image in the novel. Zaleekah meets a Nen, a tattoo artist, and learns that some people ask for cuneiform signs as tattoos. Nen tattoos the cuneiform sign for water on Zaleekah’s wrist. This is the same tattoo that appears on the forehead of the grandmother of Narin, who is about to be baptized in Iraq and features in a plot point near the end of the novel.

By painting a chilling portrait of the genocide in 2014 by ISIS in Iraq of the Yazidi people, and the enslavement as sex slaves of its young girls, Shafak shows herself as a champion for justice as in “The Island of Missing Trees.” These sections are brutal to read, a brutality foreshown by Ashurbanipal when he set his former mentor on fire. One Yazidi girl may or may not recover from the trauma of her captivity. But Shafar reminds us it isn’t over. Just like the water flowing, it’s never over.

If you want to follow Elif Shafak, you can read her essays at “Unmapped Storylands” at elifshafak.substack.com

I loved this book and like you was sent down many avenues of research about things I previously knew nothing about. I was also fortunate enough to hear Elif in conversation about the book in Cambridge and she signed my copy.

I’ve had this book on my waiting list on Libby since you wrote this review. I am now at the midpoint of the book and find it as compelling and fascinating as you promised. Now I want to read Elif’s other works

Thank you again