Each morning I receive a list of books that I can download for $1.99 through a site called bookbub.com. The offerings are based on categories I signed up for: literary fiction, historical fiction, memoir, best sellers , and women’s fiction.

As women make up the vast majority of book buyers, I suppose it’s helpful to be called “women’s fiction.” But it has a pejorative whiff, a lesser being than “literary fiction.” So what is the difference and why should we care?

Constatin Panagopoulos on Unsplash.com

I recently read an article from another online resource I enjoy called www.lithub.com. The article by Liz Kay is called “What do we mean when we say women’s fiction?” She argued that women’s fiction frequently has a plot that revolves around relationships with a female protagonist whose character matches the stories we’ve been told about who is good and who is bad. Kay found a lack of moral ambiguity in women’s fiction. The heroine’s only flaws are “feminine flaws such as being clumsy, being overweight, being plain or being temporarily undone by trauma.”

The object of the female protagonist is to be loved, respected, or successful. The books frequently have an obvious “lesson” in them. Most important according to Kay was the approach to the reader herself: She will not be required to think. Ouch!

I’d add to the list that women’s fiction often has a predictable dilemma, a predictable plot, and a happy ending. “Pride and Prejudice,” is women’s fiction. Well written and a delightful send-up of societal pressure to marry well, but it’s all about whether Elizabeth Bennett will find true love and marriage.

I have a friend (a man) who argues that Fanny Price in “Mansfield Park,” also by Jane Austen, is “heroic,” not a term generally applied to women’s fiction. He says “She defies and alienates everybody by refusing [Henry Crawford] in marriage and sticking to her guns, completely unprecedented moves for her . . . Considering her circumstances, it’s all a bit, well, heroic.” He added, “Fanny . . . has a very rich inner life but, except when she’s with Edmund, never says anything, expresses nothing. Making a character like that into the book’s center is quite a risk, and pulling it off is quite a feat.”

Kay, an author of women’s, fiction herself, adds,

“I don’t want to talk about how to be a woman in the world. I want to talk about the world we’re being women in. And more and more of the books I’m reading books by women and books for women are pushing harder and farther into that ambiguity, letting their female protagonist be humans instead of just role models..’

She added “I do write primarily for women, but what I refuse to accept is that with women as readers I need to lower the bar.”

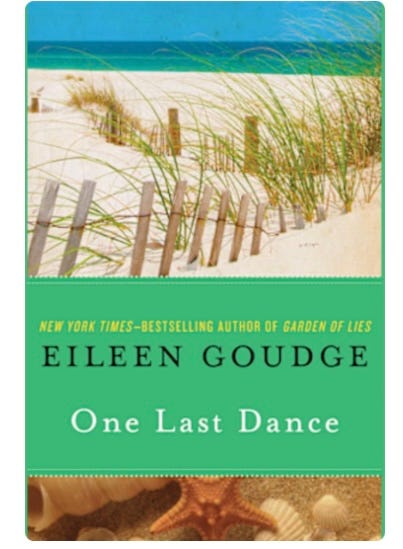

One of the things I noticed about women’s fiction is that it is often identifiable by the title alone, which often refers to a romantic setting. For example, here are women’s fiction listed by bookbub in the last couple of weeks: “Tara Road,” by Maeve Binchy, “Nantucket Nights,” by Elin Hildebrandt, “The Tuscan Sister,” by Daniela Sacerdoti, and“Sweet Salt Air,” by Barbara Delinsky.

The covers follow the titles—pastel and inviting or featuring a prominent female.

The book descriptions often include a “secret that will change their lives forever,” which feels overly-dramatic to me.

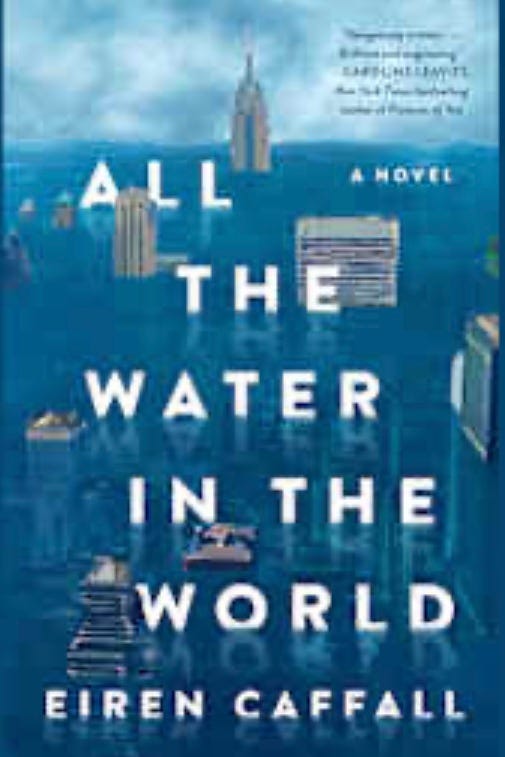

By contrast, here are the titles of a few books listed under literary fiction: “Esola,” by Allegra Goodman, “All the Water in the World,” by Eiren Caffall, and “Year of Wonders,” by Geraldine Brooks. See the difference in the cover?

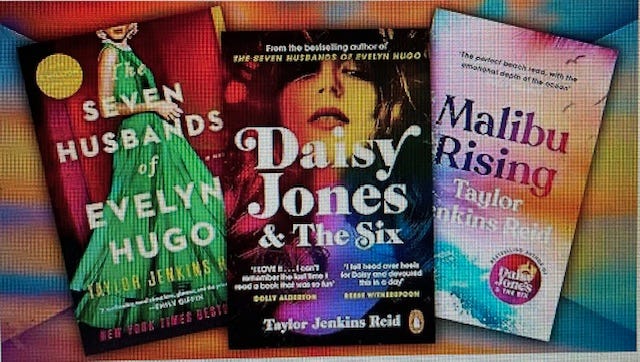

I follow a substack called Jansplaining by Jan Harayda, who talks mostly about the publishing industry (highly recommend: jansplaining.substack.com). This week she posted a piece about the author Taylor Jenkins Reid, who published Malibu Rising in 2021, which was chosen by Jenna Bush Hager for her book club. Reid has just received a $40 million contract for a four-book deal, which grabs attention.

This book is categorized as women’s fiction. Harayda added to the list of characteristics of women’s literature proposed by Liz Kay that the dialogue is often clunky. Here is an example:

"You were born a piece of shit and you'll die a piece of shit just like every other piece of shit on this planet!"

Elinor Lipman of the New York Times wrote:

"Reid's dialogue wants to capture the tone of the young, the beautiful and athletic, but much of it feels lazy to the point of being cringe-worthy. The dialogue and interior monologue can be juvenile, filled with repeated expletives that can't be quoted here, but wear thin and detract from the overall effect, rather than adding to the portrait of these characters, as Reid presumably intends.

Of course, women’s fiction can be beautifully written with great dialogue, but if it’s depending on a formula to deliver, an author can cut corners.

Jenna Bush has said that Malibu rising resembled Sweet Valley High for grown-ups, which Harayda said tongue in cheek is not a problem “if you’ve read too much Sally Rooney and crave something with fewer literary pretensions.”

Reid has said Malibu Rising is about “what parents owe their children.” But Jan Harayda concludes: “The larger question raised by this novel is what authors owe their readers, and whether it isn’t more than they get in this one.”

How can we apply these standards to other women’s fiction? Take “Lessons in Chemistry,” by Bonnie Garmus. The protagonist, Elizabeth Zott, a gifted chemist in the 1960s, encounters many predictable, sexist obstacles to her career, but eventually through the happenstance of a television show where she adds chemistry lessons into cooking lessons is able to return to chemistry.

This novel does not follow one of the expected plot lines, which is finding true love, as the love of her life dies early in the novel. But she is as stalwart and true a character as Fanny Price. And she eventually gets her chemistry lab back and the job that goes with it. Does this novel make us think? My book group thought so, although the conversation was mostly about sexist obstacles we have faced in our careers rather than the book itself.

I recently finished reading “The Book Club for Troublesome Women,” by Marie Bostwick, which I picked up at my local library after a book talk by the author. Like “Lessons in Chemistry,” it is set in the 60s. The premise is that four women living in a planned community begin a book group with Betty Freidan’s book “The Feminine Mystique.” Calling themselves “the Betty’s,” the four women continue reading and navigating issues with relationships and jobs.

One woman wanted to be a veterinarian, but abandoned her plan to get married. Another woman wanted to become a magazine writer, but chafed at writing women’s articles about mishaps in the life of the suburban housewife. A third is a nurse who already has five children with a 6th on the way. The fourth is a pill popping alcoholic, who fancies herself an artist, but eventually comes to realize that she doesn’t have enough talent to be successful.

All these women long for some self expression – and a paycheck – outside their families. I read a book review that said this book is about “the power of books, “and although their book list has a number of books that espouse feminist values, we never hear the discussion in the book group or how the books relate to any of their decisions.

It appeared that the book club was simply an organizing device upon which to hang stories about these four different women. And although it’s true that one woman writes an article for her magazine about the Feminine Mystique that ultimately gets her fired, none of these women meet the standard set up by Liz Kay for a female protagonist that would elevate a story above women’s fiction.

There is very little moral ambiguity in any of the characters. They appear to be good mothers who are interested in keeping their marriages together if they can (or throwing out a cheating spouse.) If the book aims to be instructional on women coming into their own power and emerging from their homes into the workforce, there are only the expected obstacles. We don’t doubt that they will succeed.

By contrast, look at “Manhattan Beach,” by Jennifer Eagan, set as the country was getting ready to enter WWII. Anna Kerrigan as a teenager works in a shipbuilding factory measuring parts but longs to be a diver, able work on the submerged parts of ships. She applies and is rejected because she is female. She eventually succeeds. But the story of how she learns to live on her own after her mother leaves and navigates the aftermath of a torrid sexual encounter give depth to her character. An undercurrent of mob violence and her father’s possible involvement creates tension. Her father has disappeared, a dockyard worker assumed drowned. But is he dead?

Unlike typical women’s fiction, the novel alternates between three points of view: Anna, her father, Eddie, and Dexter Styles, a nightclub owner and mob boss whom Eddie works for. There are no traditional happy endings for any of these characters, but we see Anna take control of her own life in an unexpected way. “Manhattan Beach” is classified as historical fiction, avoiding the issue of whether it is literary or women’s fiction.

Ultimately, the debate about women’s fiction reminds me that I want to read a well-written story about a complex female character with a plot that avoids the expected resolution. And as Liz Kay says, I want it to make me think.

*

If you enjoyed this essay, please click the heart to let me know you are there!

I like to read books that make me think for the most part, although there are times when a book just has to entertain me for a little while. Those "fluffy" books serve a purpose to help me de-stress perhaps, but they get annoying if I read them too often. I found Taylor Jenkins books to be rather "fluffy," although they were fun to read one at a time. I just finished reading Niall Williams "The Time of the Child," and it still has me thinking. I can't figure out how I feel about it. It was kind of annoying because the author used long run-on sentences for the most part, and the chapters were way too long, but his use of language was fun. He described people using such metaphors that they came to life and were amusing. I love reading your blog each week!! Thank you! I always end up adding books to my To Be Read pile.

WOW! Christine must have a book in hand or on a screen 24/7. I am in awe of all she reads! Vivian Shipley